by Shane McDonnell

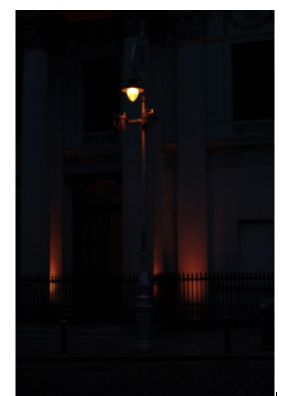

Photography by Rachel O’Sullivan. Her full profile is available in the Art & Photography section.

i.

For the longest time, and for reasons entirely unrelated to religion, I found myself unable to enter a church. I am by no means calling myself an atheist, but I wouldn’t call myself a Catholic either. Before the bestseller, I walked for hours during the summer. I only worked weekends and college was finished until September. I had a nervous breakdown of sorts not long before. I read somewhere that Charles Dickens would walk between twelve and twenty miles a day while he was writing. As was soon pointed out to me, however, Charles Dickens had very little else to do aside from attending public executions and eat mutton. I live in an age of social media and eternal distraction, to walk twelve miles a day would be an outstanding level of commitment to the craft.

The walking, to my surprise, came easy enough. I often left the house at eight in the morning and I walked four hours in one direction before I turned around and walked the four hours back again. It was the time I spent not walking that was the most difficult. I couldn’t sleep. Mam and Dad thought I was sleepwalking at night and attempted to convince me to see a hypnotist. There was no sleepwalking, however, I simply paced the kitchen when I felt sleep was beyond me. I wouldn’t quite call it therapy, as I didn’t work through the reasons for my breakdown, nor the reasons for my inability to sleep. Nor did I feel much better afterwards. I would call it a pause, a stasis. Things seemed to just take a break for the time I spent walking.

The appeal of the walking is there were rarely many people about. We live in the suburban reaches of Dublin, meaning I could walk for an hour or more without coming across a soul other than myself. I would walk to Three Rock, or Fairy Castle some days – others I wouldn’t have a destination in mind, I would simply pick a hill and walk along it until I decided to turn back.

Later on, in the summer, I stopped at a church not too far from my home. I decided to enter the church grounds and wander around. The stone path put me off, as anybody could hear me walking, so I walked on the grass to the side of the path. There was nobody about, but I kept to the grass anyway. The door to the church stood open. It was about six in the evening and there was no Mass being said and the church was sure to be empty, but I did not enter. I walked around the side to the graveyard and up and down the rows of headstones and looked out for any surnames I was familiar with. There were names I knew locally – Mulvey, O’Connor, Burns – but they all dated back to the forties or fifties. I walked around the graveyard for close to an hour before I came across a grave I knew.

JP O’Reilly – buried twelfth of May 2017 – Loved by his wife, son and daughters.

I remembered JP and how he had dropped dead of a heart attack the day before his fiftieth birthday. I was only alerted to it by a friend asking me whether I would be attending his funeral – the news had missed me somehow. I had often seen him trundling a tractor on local roads, although I heard he had sold the farm years previously. There was a white, hand-made wooden bench beside his grave with a prayer inscribed alongside JP’s name. There was bird shit down the back of it. I sat down and considered it all. I became lost in my thoughts, in a sort of trance, sitting there in the graveyard beside a man I knew just well enough to say hello to when he drove by. I don’t remember what thoughts came to me as I sat there, but when I came around and looked at my watch I had been sitting there for an hour. It was past seven and I moved homewards but I stopped again at the front of the church. The door was still open so I walked up to it and stepped inside to the smaller doors that led into the church. I pulled the ancient handle and slowly creaked the door open and peeked inside. The church was empty and lit only by the stained evening light that shone through the windows, and by the flickering red candle burning high behind the altar. A peek was enough for me and I let the door swing shut again and I turned and walked home.

Something about the graveyard fascinated me and I returned again a few days later. I still had not slept and was writing three thousand words a day, none of which amounted to even an adequate sentence. By now I was hitting nearly nine miles a day. The graveyard had intrigued me, however, and I took time out of the walking set aside especially for it. I still did not walk on the stones, so I kept to the grass again. I walked towards the opposite side of the graveyard, some of which I had not seen. I continued browsing the headstones looking for familiar names. It was more of the same. More Mulveys, more O’Connors, more Burns’. After a while, I grew tired and searched out JP’s bench once again to sit down. There was more bird shit down the back of it and I wondered if none of his children came to tidy it now and again. I became lost in my thoughts once more. When I came around I noticed another presence in the graveyard. Another man was wandering through the graves. I didn’t know whether he had seen me, so I stayed. The man stopped at a headstone and looked down at it for a moment and I wondered who he was visiting. He stood at the foot of the grave with his head bowed slightly before moving on. He turned his head and saw me sitting at JP’s grave and watched me for a moment before nodding and wandering on. I became uncomfortable after being noticed and gathered myself to walk home again. This time I did not think about entering the church, nor did I stop out front. I walked out the gate and turned towards home.

ii.

At this particular point in my life, everything I wrote was appallingly bad. We’re talking unreadable shit. In my battle to sleep at night, ideas arrived partially formed, like embryos. Over the next day or two, the idea would mature in my head as I walked, and fulfil their potential. Something would catch my eye, a squirrel jumping between tree branches or a condom dangling from a bush. Something inside would click and I knew I had a story. I would come home and batter the keyboard and bleed out the sharpest translation of this idea I could muster. Then I would collapse into bed and wait for morning to arrive. I would read back on this work the next morning, and it would amount to nothing more than complete gibberish. Sentences that hadn’t a trace of sense about them, coupled with what appeared to be words completely of my own invention – but not in the Shakespearean genius kind of way. Until the point of my nervous breakdown, I had written a handful of presentable stories. Nothing to set the world alight – there would be no conservative Christians burning my work in a bonfire – but I was quite pleased with some of my work. I had excelled at English in school, at essay-writing in particular, and had decided during my Leaving Cert that I would pursue a career writing fiction. It was not until after I left secondary school that I realised that Leaving Cert essay-writing had not one single common characteristic with writing fiction. Flowery language was not enough – as a matter of fact, it was the opposite of enough. My work was gleefully rejected by each and every literary journal in Ireland, and referred to as “too polished.” Profound plotlines exploring the true meaning of love were quite the opposite of what was considered competent, even acceptable, in the literary world. To make the sort of impact I wanted to make, I needed to start all over again. I took on an absurd mixture of pointed Dublin lingo and slanty Western syntax in my work. I wrote not about love triangles or innocence, but about humorously violent murders and irrationally sexy heroin addicts. My work did not go down well among every literary circle. But with those who took it on – oh they ate that shit up. My work had found a home in emerging magazines of fiction and I built relationships with editors who were all too happy to take on my work.

Halfway through giving a presentation on behalf of my group in front of a packed lecture hall as part of my summer exams, I began to weep. I excused myself from the room and walked to the bathroom where I locked myself in a cubicle and fell into a shrieking fit. I was eventually rescued from the cubicle, lying in a pool of my own piss and brought to the St John of God’s mental. I spent a week there before returning home. I had not slept since then, nor had I strung together two convincing lines of prose. The walks were, I reasoned, fending off my looming capitulation, even if they did not result in admissible writing.

iii.

Having been noticed sitting at JP’s bench, I avoided the church. I was uncomfortable at the idea of somebody knowing I was there. I resumed my hillwalking, I was approaching eleven miles a day – still producing writing of abhorrent complexions. However, thoughts of the graveyard and of JP’s bench quickly re-entered my mind. I found that, for the length of my walks and for all the nature that I encountered, my thoughts continually wandered back to the graveyard. I returned again, avoiding the front of the church and taking the long way around – as if to remind myself of the layout of the graves. I noticed fresh flowers on certain graves and walked a lap of the path around the graveyard which would bring me to JP’s bench. I wanted to sit there and be lost among my own thoughts once again. I arrived at the bench, it appeared to have been wiped down in the meantime and the bird shit was gone. Fresh flowers sat up against JP’s headstone, which made me uneasy. If JP’s family had visited in the last few days, it meant the possibility remained that they would visit again soon. The idea of being found sitting beside the grave of a man who I hardly could call a friend, by his own family no less, gave me a taste in my mouth like metal. There was a certain pull off the bench though, and it convinced me to stay. I fell into a trance once again.

Not long after I began to daydream, I was disturbed by a movement. A man sat down on the bench beside me and relaxed into himself. I stiffened, not knowing what to say or do but look at the man who had arrived out of the sky. Beyond my mother and father, and the paltry words between ordering a coffee and paying for it, I had not been in contact with another human since the breakdown. He sat wordlessly for a minute or so, the two of us suspended in time. Him not saying anything, me unable to move. I wanted very much to stand up and walk away and never think about the church or the graveyard again.

“Grand day for a walk, all the same,” he said. “But you wouldn’t want to be out for much longer.” He pointed to the distant sky. “It has the look of rain off it.”

I neither agreed nor disagreed with his observation but I stared straight ahead at JP’s grave. The flowers resting against his headstone. When I thought he was looking away I stole a glance at this stranger and knew at once, beneath his hat and his coat, that this was the old man who I had seen the other day walking between the graves.

“What’s the deal with yourself?” he asked. “A bit young to be bothering graveyards this regularly, aren’t you?”

I had no words to answer his question, or maybe I just didn’t know where to start. I tried to talk but what came out was an array of stuttered mumblings before I gave up and turned my head again.

“I see,” he said, “you’re one of them mental cases aren’t you? I knew a fellow like that once, he jumped off the M50 Bridge at Cherrywood. Nice man all the same.”

I felt a burning desire to shriek at this man to get the fuck away from me, to spit in his face and claw his eyes out. There was something about him that made me squeamish. The taste like metal returned. I felt another breakdown come on.

“I knew it,” he said. “I can see it in you. Go on so, what’s the deal? Psychosis, Schizo,” he said, “Bipolar?”

I looked at this man who tormented me. He appeared amused by the situation, he seemed to be enjoying it.

“Are you trying to insult me?” I asked.

I tried to visualise my route out of the graveyard in case this man tried to kill me.

“Not at all,” he said, “I’m just making conversation. I hate small talk. I like the meatier stuff,” he said.

I looked at this man before me. He resembled what I thought a rapist looks like when I was a teenager, but that no rapist has ever looked like. He wore a mid-length, dark grey trench coat with suit pants and shoes that may have been smart at one point in time. I realised that on his head was a fedora. A fucking fedora.

He searched his pockets and emerged with a box of Rothmans.

“Cig?” he asked.

I rarely smoke but I took one anyway. We sat in silence except for the puffing of our smokes. Then he spoke again.

“Have you ever considered the possibility that none of our choices are our own?” he said.

I looked at him. It is true that I had often considered this, but was not sure whether it would be wise to confess it. I nodded and dragged off the cigarette.

“Yeah,” he said, “you seem like the type. Well let me tell you, kid, none of our choices are of our own doing. We are all influenced by one thing or another and there’s nothing you or I can do to change it.”

I felt him looking at me and willing me to engage with him but I stared straight ahead and sucked on my Rothman.

“You don’t believe me, do you?” he said, “I’ll give you an example. That buddy of mine who jumped off the M50 Bridge, that was not a choice of his own making. I know for a fact that every night when he went to bed,” he said, “his housemate knelt beside his bed and whispered into his ear for hours. I don’t know what he whispered, it could have been gibberish, but I’m certain that somewhere in all that whispering, he convinced him to jump off the M50 bridge. This only went on for a month or two before my buddy killed himself. See what I mean?”

The old man finished his Rothman and flicked the butt. I did not see what he meant. It landed in the stones that covered JP’s grave and I watched the smoke rise off it. I mumbled that I had to go, I had somewhere to be. The old man offered me a Rothman for the road which I accepted and dragged long from as I left the graveyard. I stood outside the gate and got a headache but I wasn’t sure if it was my encounter with the old man that caused it or if it was the spinnies from the Rothman.

I walked home and sat in my room for the night hammering my keyboard once again – I was surely breaking records for typing here. I managed over five thousand words that night. I wondered how much writing was too much writing. Sleep was still well beyond my clutches and I sat up all night letting my playlists shuffle at random. It still amazes me how quickly the hours seemed to run from me at night. Though I still wasn’t sleeping, the hours between midnight and seven o’clock slipped away from me every night and, before I knew it, night had rolled into day once more.

iv.

My encounter with the old man made me uneasy but exhilarated me also. I abandoned my lengthy wanderings and walked exclusively to the church each day. I did not see him, however, for the following week or so. I still could not sleep and so the days stretched out like the summer light. I had several unopened emails from my college professors. My diet now was made up entirely of Cheerios and coffee. I wrote like a motherfucker. I’m surprised my laptop survived the ordeal as I molested its keys for hours every night. It was about ten days after my last encounter with the old man that I found him in the graveyard. This time he was there already, sitting on JP’s bench. I wandered by the front of the church, not bothering to take the long way around this time, but still keeping to the grass. He smiled warmly and gave me a look that asked what kept you?

“I was wondering when I’d bump into you again,” he said.

I asked him why.

“You’ve the look of someone fascinated by all this death,” he said, “Our kind tend to linger around these places more often than not.”

I sat beside him on the bench and he opened a rucksack that rested by his feet.

Our Kind?

“Can?” he asked, holding a can of Galahad Export out to me.

I told him I wasn’t sure we’re supposed to drink on church grounds.

“Since when were you the fucking caretaker?” he said. I took the can and we sipped quietly on JP’s bench. “What’s your story then?” he asked.

I wasn’t entirely sure what he meant.

“What are you doing with yourself,” he said, “are you working or a student or do you dedicate your time exclusively to haunting graveyards?”

I told him I was at University.

“What are you studying?” he asked.

I told him I was studying English Literature.

“Aha!” he roared suddenly, “I knew there was a cunty sort of a look to you.”

I didn’t know how to respond to this, so the old man continued.

“I bet you call yourself a writer too,” he said. “You’re probably one of them shitehawks who always talks about Ulysses without ever having actually read it, aren’t you? “

It was true that I had not yet read Ulysses, but I was getting around to it. My face said it all.

“I knew it,” he said, so go on, what is it you write? Poetry, I bet.”

In my younger and more formative years I had dabbled in poetry. I spent a considerable amount of time locked away in my room scribbling heartfelt notes about girls and suicide. My poetic endeavours, however, never extended beyond this sort of thing. Ireland, I determined, was fucking crawling with poets, and it would not do to waste my time on such an endeavour.

I told the old man I wrote short stories.

“I see,” he said, “not entirely condemned to hell then are you?”

It was still early enough for the graveyard to have visitors, and an elderly woman shuffled along the path on the other side. She held a bouquet of flowers and was alone. The old man thundered on beside me.

“Writers,” he shrieked, “are the lowest of the fucking low. To be so arrogant as to think anybody else wants to hear what they have to say – and to have the burning fucking audacity to charge them money for it?”

He had a glint in his eye like murder.

“Every single one of them,” he roared, “shall suffer the true wrath of God, if there is such a thing.”

The elderly woman at the other side of the graveyard heard this and turned to stare in our direction and I became uncomfortable.

“You might be surprised to know, however,” he said, “that I was a writer at one point.”

I looked at him.

“Yes,” he said, “and not too bad either. I was published in my twenties. The first book wasn’t bad, but I was still finding my feet. The second one is where it really took off. The critics fucking creamed themselves over it. It flew off the shelves. I was Ireland’s next big literary promise. It was longlisted for a Booker. There wasn’t a publishing house in the English-speaking world who didn’t want to sign me. The third book was a modest follow-up, he said. Nothing too special but well-received. It was while working on the fourth one that shit really hit the fan.”

It seemed to me as if the old man had somehow forgotten my presence, and when he looked at me he startled for a moment before remembering where he was.

“The fourth book,” he said, “was a fucking nightmare. That’s when my wife lost her mind. She arrived home like a tornado in expensive make-up and brought all nine circles of hell in with her. She roared every accusation imaginable in my direction,” he said, “and me sitting at my desk with the pen still in my hand.”

The old man recounted this story and I sat listening to him, sipping the can of Galahad Export.

“She screamed and screamed at me, calling me a cheater, a murderer, a thief. She claimed,” he said, “that I had killed her father a year previously and covered it up as a heart attack. And what’s more, she accused me of doing it all so as to have material to write about in my books. Crazy bitch,” he said.

The old man appeared to be in a trance once again. I sipped at my can until it was empty and the old man gave me another. His wife, it turned out, took the manuscript of his fourth novel and threw it into the burning fireplace.

“I never saw her again after that day,” he said. She ran out the door and never came back again.”

The old man looked at me and offered me another Rothman, which I took. The old man told me that he never wrote another word after his wife walked out.

“Writers,” he said, “fucking writers, are the most doomed motherfuckers of all of us. Read Ulysses now, kid, while you still can. Just read it and never say another word about it ever again.”

I felt that it was time to head home again and I thanked the old man for the cans and I stood up to leave. He offered me a Rothman, which I refused.

“I might see you here again soon,” he said. I nodded and waved and walked on the stone path to the gate in front of the church. The church doors were still open, but I decided against looking inside. I walked homewards again, finishing my can and crushing it on the tarmac.

V.

I did not return to the graveyard or the church after that encounter with the old man. I arrived home that evening and did not recede into my bedroom to type away for the night. Instead, I sat in the kitchen and listened to the radio as my mother prepared dinner. That night I felt asleep for the first time since the breakdown. I awoke the next morning with no words typed but the feeling that something had clicked inside me, either into or out of place, I wasn’t sure which.

I began to work on what felt like worthwhile writing, and before long I had reestablished contact with editors of various literary journals. They agreed to take on my work and I became more thoughtful and more disciplined. Before the end of that year I had completed my first novel, which was taken on by a small independent publishing house in the City Centre. My novel received top reviews and sold reasonably well. I won a Hennessy and I was signed by one of the top publishers in the country for a multi-book deal. My next two novels were bestsellers and the third was shortlisted for a Booker. Walking is still a part of my routine, although I keep it to a few kilometres now. Charles Dickens, I determined, simply had too much fucking time on his hands. I still have the thousands of words I wrote during my many sleepless nights. It’s all in a folder, tucked away in a drawer beneath the rest of the first drafts and scribbled notes that never amounted to anything. I haven’t looked at them in a very long time. The thought gives me a taste in my mouth like metal.

Shane McDonnell

Shane McDonnell is a writer and student from Dublin. His work has appeared most recently in Silver Apples Magazine, Caveat Lector and ‘Brevity is the Soul: Wit from lockdown Ireland.