By Aisling Lee

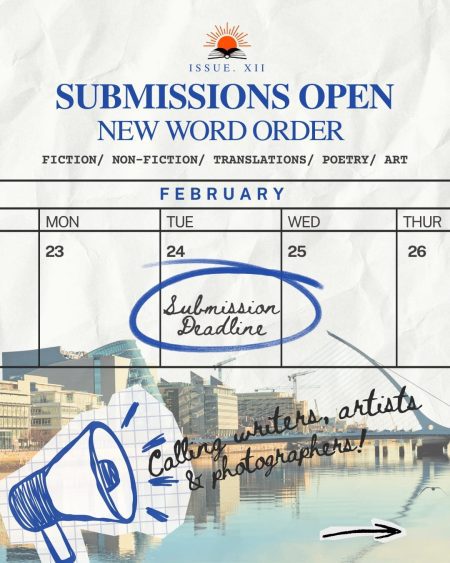

Photo “City Lights” By Eoin Campbell

Eloise sat with her mother at the table in the kitchen, where the only sound was the soft hum of the fridge. Her gaze hovered over the bowl of beef stew in front of her, from which she had taken a mere half dozen spoonfuls. The spoon hung vertically over the bowl, its handle in the loose grip of Eloise’s slim fingers.

Sitting back in her chair opposite an empty bowl with a spoon resting in it, Roberta eyed her daughter pensively.

‘What if I were to go vegetarian?’ Eloise asked, taking Roberta by surprise. She didn’t look up from her bowl.

‘It’d make things difficult,’ her mother replied, seemingly unmoved.

Eloise smiled and swung her spoon gently from side to side as if it were a medallion which she hoped might hypnotise her stew out of existence. ‘But it’d be my beliefs,’ she said. ‘My morality. You’d have to accept that.’

‘I wouldn’t have any trouble accepting it. It’d be cooking for you I’d have difficulty with. Might have to stop. Leave you to fend for yourself.’

She knew that her daughter’s hypothetical was indeed just that. She was teasing. Turning vegetarian wasn’t on the horizon for her, and Roberta was sure of that. She watched her, still smiling sedately, still avoiding eye contact, still contemplating taking her next mouthful but refusing to take any action.

‘Guess I’ll have to wait till I go to college then. I’ll have to cook for myself then anyway.’

‘You’re a full ten minutes into life as a vegetarian now. It’s been so long since you’ve touched your stew.’

Eloise shrugged.

‘Don’t you like it?’

‘Just not that hungry.’

‘You never are, are you? Look at you. You’re nothing but skin and bones. And as white as a goddamn sheet.’

As soon as the words were out of her mouth, Roberta hoped she hadn’t sounded like she was losing her temper. She wasn’t trying to be critical, and besides, she knew better than to try to win her daughter over that way.

Finally, Eloise looked up at her with her wide dark eyes. It was true that she had a sickly look about her. Her long, chocolate-coloured hair was thin and limp, and although her face was pretty, to examine it was to get the feeling that it was missing something – warmth of colour, plumpness in the cheeks, exuberance.

While Eloise looked sadly untouched by the ebb and flow of life, Roberta appeared to embody its vivacity and colour. Her tanned skin was mottled, pock-marked, and wrinkled around the eyes, on whose bottom lids she smeared navy blue eyeliner every morning to supplement the thick layers of mascara on her top and bottom lashes. She kept her bouncy, curly hair trimmed to earlobe level and dyed light pink.

The pair looked nothing like mother and daughter.

Eloise begrudgingly took three more spoonfuls of stew in quick succession, then said, ‘ ‘S gone cold.’

‘I wonder how that happened. If I spin it in the microwave for you, will you eat it then?’

Eloise stretched her arms downwards, pressed her hands together and gripped them between her knees. She looked up at her mother coyly, then shook her head.

Roberta huffed and rolled her eyes. ‘What am I going to do with you, sweetheart?’

‘I’ve eaten, like, half, probably. I might reheat the rest later.’

‘OK. Do that, then. If you haven’t by eight or nine o’clock, I’ll come after you to make sure you do.’

‘OK. Thanks, Mom.’

‘You’re welcome.’

Eloise pushed her chair back slowly from the table. ‘Gonna go do some homework now.’

Roberta pursed her lips, closed her eyes briefly and nodded. ‘OK,’ she said, in a whisper, as if she had just been informed of some difficult truth.

Eloise rose from her seat and pushed it neatly under the table before throwing her mum a sweet, half-hearted smile. In her stockinged feet, she padded out of the kitchen and down the hall to her bedroom.

She closed the door and straightaway picked up her phone from the bedside locker. She had a message from Shannon, ‘You done the maths homework?’, which she disregarded. There was no word from Nathan, but that didn’t surprise or bother her. Their plans had been agreed, but she sent him a message to confirm anyway, knowing that he might not bother to reply.

‘Am I still gonna see you at the church tonight?’

The symbol indicating that he had seen the message appeared immediately. That still didn’t mean he was going to reply, she knew. But he did.

‘Only if you turn up yourself like’

‘Lol cool’

She placed her phone down, perched on the side of the bed and opened the middle drawer of her nightstand. From the very back, she pulled out a small box, turning to glance at the door as her hand emerged with it, ready to shove it back inside if Roberta appeared. Assured that she was alone, she slid open the matchbox and examined the contents. Four cigarettes and about a dozen matches, the former all stolen one at a time over the course of a week from Roberta’s stock, the latter her own, for lighting the cherry-scented candle on her desk. Nathan was sure to have a lighter, so she probably wouldn’t need the matches, but she figured it was best to be prepared.

She replaced the box and picked up her phone again to check the time. 18:14. She had agreed to meet Nathan at half eight, and it would take her ten, maybe fifteen, minutes to walk to the church ruins at the edge of town. If she didn’t want to be caught, slipping out without first appeasing her mother by finishing her dinner was out of the question, so Eloise resolved to return to the kitchen at a quarter to eight. She would dutifully finish her stew, then wish Roberta goodnight, saying she had a lot of homework still to do and would go to bed straight after.

In the intervening hour and a half, she decided, she should probably actually do some homework.

At 7:45, she found Roberta in the kitchen, flicking idly through a magazine. She looked up when she heard Eloise entering.

‘You finally hungry?’

‘Meh.’ Eloise shrugged.

Roberta shook her head in disbelief but smiled. ‘My girl,’ she said, in a tone suggestive of subtext: I do wonder at you sometimes.

She wondered what Eloise’s dad would make of his daughter’s poor appetite and then whether it would be so poor at all if she had him in her life. Could he have filled her childhood years with joyous occasions of breaking bread together and thus led her to associate food purely with pleasure? Meditations on what their life as a nuclear family might have looked like crept into Roberta’s mind every single day.

Eloise had never known her dad, had no idea who he was, and the story Roberta told her was that she wasn’t sure either. So whenever the subject came up, she let her daughter gently tease her about what must have been a string of wild nights in February 2005.

She had been caught off guard by how quickly Eloise had grown up and reached the point where she needed more explanation than, Not everybody has a dad, sweetheart, and that’s OK. If she had been more prepared for that moment, if she had taken time to consider how she would break the truth to Eloise and how much of it she would tell, she felt sure that she would never have told an outright lie. Every day, she cursed herself for the fact that that was what she had done.

After spinning her dinner in the microwave for three minutes, Eloise brought it back to the table and made her way through it in sips and nibbles, showing little more enthusiasm than she had earlier.

‘Have you finished your homework?’ Roberta asked.

‘No, not yet.’ Eloise grabbed her opportunity to feed her mother her casual lie. ‘I’ll go back to it after this and then just go straight to bed, I think. I’m pretty tired.’

‘It’s no wonder, El. You’d have more energy if you ate more.’

‘Well, look, I’m finishing my dinner now, aren’t I? And it’s not like I’m always tired. I’m fine. It was just a long day. Lots of homework, and I was tossing and turning a bit last night. That’s all. I’ll be fine tomorrow after an early night.’

Roberta gazed at her daughter sympathetically. ‘All right.’

When she had finished her dinner, Eloise took her bowl and spoon to the sink and then kissed her mother goodnight on the top of her head.

‘Goodnight, love. And do go to bed early, won’t you? Don’t spend too long studying. Your rest is important.’

‘I know. I won’t. Night.’

‘Sleep well.’

It was now 20:11. Back in her room, Eloise pulled on her black Converse, packed her matchbox and some cash into a small handbag, and then checked herself in the mirror. She tugged at her lank hair and tried to plump it up a little, but it just fell flat again.

‘Fuck it,’ she whispered to herself resignedly.

On the spur of the moment, she pulled out a black eye pencil from the top drawer of her dresser and ran its nib hastily over her top and bottom eyelids, then used a finger to blend its markings to make them appear less severe, more imperfect, and effortless.

She picked up her phone and ignored another two messages from Shannon: ‘Hello?’ then ‘Fuck it, nvm’. It was 20:18. She dropped the phone into her handbag, zipped it closed and then climbed up onto her bed, over whose headboard was the room’s only window, which opened wide enough for Eloise’s slight form to slip out easily.

She landed almost silently on the tarmac. It was impossible to seal the window shut from the outside, but she pulled it closed behind her as best she could. The night was a heavy shade of grey and would be pitch black by the time she got to the church.

She could get there via the humble streets of Gortnaspeel town and down the lane next to the row of old terraced houses whose back windows overlooked the church in the distance. But there was a sense of escape and freedom associated with cutting across the back fields instead. This would also eliminate the risk of running into any of her mother’s friends in town, who would surely suspect her of having snuck out and then report back to Roberta, no matter how firmly Eloise might insist that she had her permission to be out.

The churchgoers of Gortnaspeel attended St Michael’s, a fine stone building though reasonably modest in size, situated about three miles from Gortnaspeel and five miles from the neighbouring Kilfarrock. The church right on the edge of Gortnaspeel for which Eloise was headed had been in ruins for the past couple of hundred years and certainly wasn’t going to be rebuilt any time soon. But, the graveyard on the grounds had been in use until only fifty or sixty years ago.

Using the torch on her phone to make sure she didn’t trip over any gravestones, she made her way towards the church entrance. The doorway was still plainly defined and had two squat steps leading up to it, but other than that, the building consisted of nothing more than four walls of uneven height. The corner between the back wall and the right one looked like it had been rent apart from the top, as the two walls only met at the very bottom. It was a bleak spot but also peculiarly attractive and enticing.

Eloise stepped carefully up to the church’s entrance and shone her torch inside.

‘Nathan?’

She scanned the four corners, then stepped outside again and circled the edifice, hoping that Nathan wasn’t intentionally hiding somewhere and about to jump out and frighten her.

The display on her phone told her it was only 20:33. Most likely, he hadn’t arrived yet. She returned to the steps at the doorway and sat down, deciding then that she would use this time to acknowledge Shannon’s messages. All she did was send her the emoji with its tongue sticking out. Then a message arrived from Keva, which simply said, ‘Hey wua?’ Ignore. Eloise couldn’t understand why people sent messages asking pointless questions when they had just seen her in school that day and would again tomorrow.

She slipped her box of cigarettes out from her bag and opened it, regarding them like they were precious gems which she had stolen and couldn’t afford to lose. The first and only time she had smoked had been with Nathan, outside the youth club at the end of a disco. She hadn’t enjoyed it much but was pretty sure it impressed him, and she wanted to get used to it.

She would wait to light up until he arrived. He’d be sure to have his own, but in case he didn’t, she had two for herself, two for him, and he would be immensely pleased with her for coming prepared.

Roberta washed up the bowl from which Eloise had reluctantly eaten her stew and left it carefully on the drying board.

Would she ever, she wondered, find the courage to tell Eloise the truth about her dad? With every day that she didn’t, the prospect seemed more and more daunting. Of course, it was wrong of her to lie, but she had done so in a panic. Would it be more unfair to allow Eloise to continue believing the lie or to burden her with the double upset of the truth and the fact that she had been lied to?

Roberta had told Eloise that of the several made-up men whom she believed to be her possible fathers, she never saw any of them again, had contact information for none of them, and for some, only knew their first names. Not one of them, she assured Eloise, would be capable of loving her as she did, and it, therefore, wouldn’t be worth the inestimable lengths to which they would have to go to track them all down and run paternity tests.

But that was all bullshit.

The truth was that Roberta and Eloise’s father had had a brief but sincere and committed relationship, right up until he took his own life only, a few weeks into the pregnancy before either of them even knew about it. Roberta still missed him every day, and it particularly stung when Eloise smiled in a certain way – raised her light eyebrows, lifted her chin slightly, showed her small teeth behind thin lips – and Roberta could see David’s face in hers, clear as day.

He was buried at St Michael’s church along the road to Kilfarrock, but that wasn’t where Roberta visited him.

The grave of his great-grandfather, his namesake, David Bolger, was at the church ruins. When he pointed it out to Roberta, he had remarked that it felt strange to see his name on a gravestone, and she now visited him there because it was a place where they had spent time together. Although, of course, she had attended David’s funeral, she sat relatively unnoticed at the back of the church and left immediately after the service because she barely knew his family. It wouldn’t have surprised her if they had, in fact, seen her there but failed to remember who she was. So she had never even seen his grave and didn’t care to seek it out in case she might run into his mum or dad or one of his sisters who, she felt sure, would regard her as having little right to be there.

David Bolger Senior’s grave held more meaning for her. David’s comment about seeing his name on a gravestone now seemed like an uncanny premonition, or perhaps he was then already plagued by the suicidal thoughts which he had never disclosed to her, and had been making plans. Either way, she felt a greater connection to the old grave at the ruins than to his actual resting place, and it was a grave only visited by her. Those who had known and missed David Senior were now all dead themselves.

She hadn’t visited it in almost a year, and suddenly she felt an overwhelming desire to do so.

She thought of Eloise, sitting in her room studying or possibly in bed with her book or her headphones by now. It was 21:19. Roberta hoped she wouldn’t sit up too late and would get a good night’s sleep. She’d be OK if she snuck out to visit David, wouldn’t she? If she made sure to close her bedroom door before she left, then Eloise would assume that she, too, had retired to bed should she leave her room for any reason.

And what if…? Roberta’s heart started to beat a little faster as she thought, what if I even climbed out through the bedroom window? That way, she could be sure Eloise wouldn’t hear her leaving. It seemed a drastic measure for a woman in her forties, but then, what should stop her? Social convention? It never had before.

She wouldn’t be long. She’d walk – through the town. Ten minutes out, ten minutes there, ten minutes back. She could be back before ten o’clock.

He who hesitates is lost, she reminded herself, and after hurriedly pulling on a jacket and shoving her phone into one of its pockets, she crept into her room, closed the door and opened the window. She discovered that she was barely dexterous enough, but in the end, managed to worm her way out into the night air, not once pausing to give herself a chance to change her mind.

‘No lighters in your house, no?’ Nathan asked in a good-natured mocking tone as he eyed Eloise’s matchbox.

She slid it open, and he caught sight of the cigarettes.

‘Well yeah, like, my mom has one, but she’d miss it straight away if I took it.’

‘They her fags too?’

‘Yeah.’

Nathan slipped a full pack of cigarettes from the pocket of his hoodie.

‘What the fuck?’ Eloise said wearily. ‘How do you get them?’

‘My brother gets them for me.’

‘How old is he?’

‘Twenty.’

Nathan pulled out a single cigarette in the loose grip of his thumb and forefinger, then took it between his lips. When he placed the box back in his pocket, his hand emerged again, holding a lighter. He clicked it to life.

‘And he’s OK with you smoking?’

‘He has to be,’ Nathan muttered, still with the cigarette protruding from his mouth. He smirked. ‘Don’t make it easy for him, y’know?’

‘The fuck.’ Eloise took the lighter from him when he passed it to her and placed one of Roberta’s cigarettes between her lips. ‘What, d’you threaten him or something?’

‘Or something.’

‘Jeez.’

Eloise handed Nathan back his lighter, and they both sat on the church step, dragging and puffing, sending out twisted transparent ribbons, which quickly dissipated in the moonlight.

As Roberta reached the graveyard, she felt sure that she would have changed her mind about coming if she had spent one more minute at home. She had left Eloise home alone before, of course. She was heading for sixteen. But she had never left her without first letting her know that she’d be on her own. What if she needed her for something? What if she became unwell and turned the house upside down, looking for her mother to comfort her?

What had she been thinking? She could have at least told her she was going out and just lied about where. He who hurries is foolish. She considered turning back. Eloise needed her more than David did. But she had made it this far, and it would be ten minutes before she could get home anyway. What was two more if she paid a flying visit to the grave? Eloise will be fine, she told herself. Eloise would be fine, and she would feel better for having taken a moment for herself and David.

There was a steady incline from the entranceway to the church. David’s grave was right of centre, about twenty yards opposite the church front. The engraving was distinct and clearly discernible under the white light of the moon. David H. Bolger. David and his great-grandfather even had the same middle initial, although David Senior’s stood for Henry while her David’s stood for Hugh. She disregarded the lifespan that was recorded as 1899-1972. If there was an afterlife, if spirits existed, David Hugh was here with her, not waiting in vain for her to turn up at the graveside three and a half miles away.

‘You’ll never guess what I’ve gone and done – to come and visit you tonight,’ she whispered. ‘Only left our fifteen-year-old daughter at home alone without her knowing I’m gone.’

…

‘Yeah, I know she’ll be fine. But I’m not staying long, OK? In case she comes looking for me. She’ll be fine, but she’d get a fright if she couldn’t find me; she – She’s a good girl, you know. A great girl.’ Roberta started to choke on her words, and tears stung her eyes. ‘She’s our girl. Ours. And God, she’s so like you. That smile, I swear… I j– ’ She sighed. ‘How can I still miss you so badly when you’ve been gone so long? God, I miss you so fucking much.’

Roberta jumped suddenly at the sound of a soft, playful yelp and looked up toward the church. The doorway was lit up as if by a miniature floodlight hidden from view. A young girl of a slight build with long dark hair had her back up against the left side of the doorway’s arch, and a young man was clutching her by the waist and sucking greedily on her neck. She lifted her chin to allow him greater access, and her arms were wrapped loosely around his neck.

Roberta then guessed that the light was that of a phone’s torch, a phone propped up against the opposite side of the arch.

Eloise squealed again and exhaled loudly. It occurred to Roberta that while the boy clearly had one of his hands pressed against her hip, the other could be anywhere, doing anything he liked to her daughter’s body.

‘Our girl,’ she whispered to the grave sedately.

A strange kind of numbness surged through her body from top to bottom, and a ball of nausea settled in her stomach.

‘She has no idea.’

Aisling Lee

Aisling Lee is a 26-year-old writer from County Longford. After graduating from Trinity College Dublin with a degree in English Literature & Psychology in 2019, she completed her M.A. in Writing at NUI Galway in 2021. Since then, while working part-time as a medical secretary, she has been furthering her portfolio, with a particular focus on short stories and creative nonfiction. In December 2022, her short story “Where There Once Was Love” was awarded second prize and published by the Australian organisation, Letter Review.