written and read by Lia Mulcahy.

It would not take a skilled hunter to follow the trail that my wife had left in the foyer.

Her heels had been neatly stepped out of, her pale scarf draped over the bannister like a sheaf of woven moonlight. The chaise lounge that I like and my wife tolerates is by the staircase, and her mink coat has been thrown over the back of it. If I were to press my nose to it, I know it would smell of a perfume that had not been in production for thirty years.

There is also an emerald tie lying forlornly on the ground. I only wear red ties, or black for funerals.

The further up the stairs I go, the more of my wife’s spoor I find. My footfalls echo on the marble, but the house is otherwise gelid, grave-still. I worry. It is unlike her to be so careless with her belongings, but she had told me that she was ill – that I ought to hurry to work and let her slumber on. She told me she’d keep herself occupied. It certainly seems she had.

I step over a man’s white shirt, crumpled on the carpet like an etiolated lily, and into the master bedroom. My stomach rumbles mutinously. I’d skipped lunch to come home early, to tend to her.

The room is dark, and familiar furniture casts menacing, humped shadows as I creak open the door. A thin shaft of light spears directly onto the carnage of the bed, revealing a chimeric tangle of sheets and waxen limbs. Lots of bodily fluid, which is a pity. It will almost certainly stain, but best not to mention it yet. No doubt my wife will be penitent when she wakes.

I approach the bed with the soft tread of someone trying not to startle a bird or a doe. My wife is very still. The gentle slope of her white shoulder melts into the sheets, and her hair falls in a rich inkspill.

The blonde head beside her does not stir. I ignore it, and lean low to the seashell curve of my wife’s ear.

“Hello, darling,” I say softly, letting my tongue curl lovingly around the endearment. “I’m home.”

A slow second passes, molasses-sweet with anticipation; then her eyes flutter open, as gracefully as if she were the heroine of a faery tale, lying in enchanted repose. She sighs. No drooling or sluggish snorting from her – my wife is the picture of elegance in everything she does, including wrestling in our bed with other men.

“Honey,” I say. “How’re you feeling?”

She looks at me, and I watch what slides behind her eyes, fast as a heartbeat – sleepy confusion, affection, stabbing realisation, and finally, guilt. There is a smear around her mouth that could almost be red lipstick.

“Shit,” she hisses. When I catch her off-guard like this, I can hear the old country in her voice; a land of dense, secretive forests, crumbling castles, and bitter winters.

“None of that.”

“Shit,” she repeats, stricken, pushing herself up to her elbows. The sheets slither free. Her accent sharpens the words like spearheads. I ease her back down with a gentle hand as she continues; “My love, I am so, so sorry, I was careless… the sheets... oh, I have left a terrible mess for you, haven’t I?”

“Hush now. You weren’t well, and you weren’t thinking clearly. Nothing to apologise for.”

“You are too good to me by far,” she murmurs, and presses a pallid hand to her forehead in dismay. The movement dislodges the position of the blonde man beside her, who stares sightlessly at the ceiling. “I have ruined the bed. And I have prepared nothing for your dinner.”

I shrug. “It’s the modern age, my darling. Men cook now, or so I’ve heard. I’m glad you’ve eaten, that’s all.”

She wipes delicately at the corner of her mouth, and most of the red flakes off easily enough. “I feel all the better for it.”

“Good.”

She watches me tenderly. Her teeth shine when she speaks.

“You must be hungry, my love.”

“A little,” I tell her, and reach across her to drag the corpse closer. The dead man’s head lolls, a slow, lugubrious motion; his neck has been torn open like the skin of an overripe orange.

My mouth waters.

“There’s leftovers,” says my wife, smiling with all of her lovely sharp teeth. “Help yourself.”

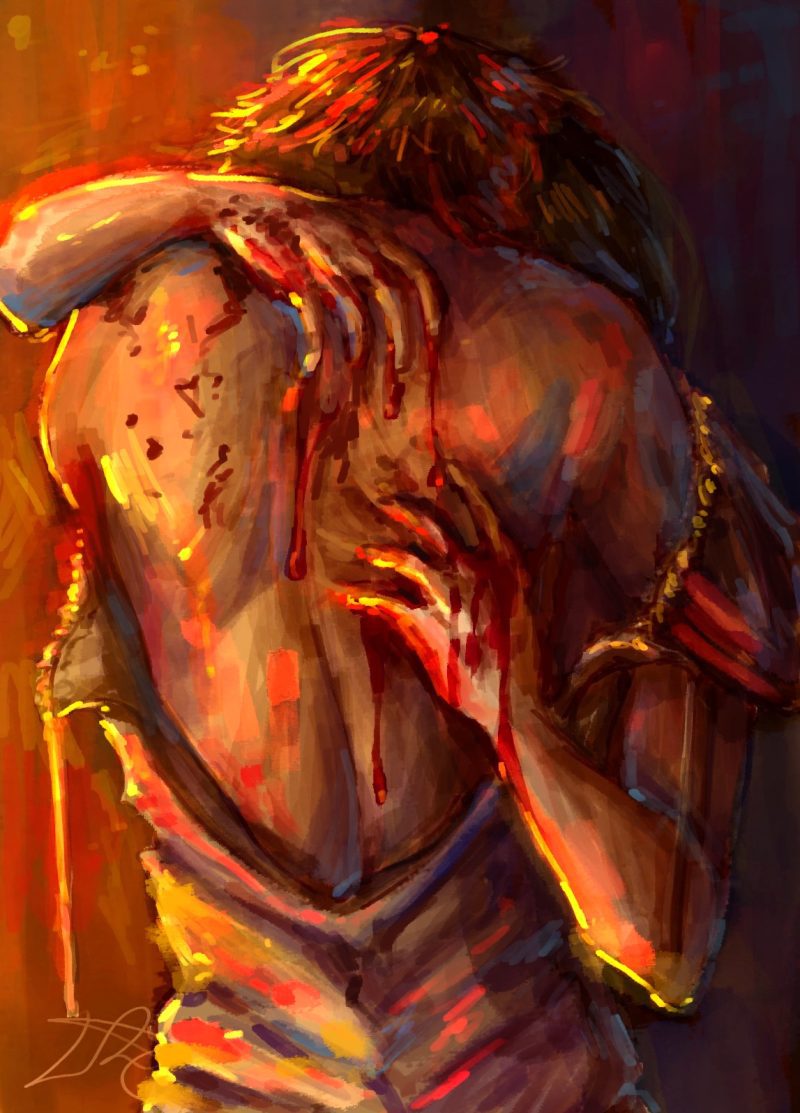

Image: Traitor. Lucía Román, Digital Illustration